The True Meaning in Memorial Day

A burial at Arlington National Cemetery in 2008 for Sergeant Major of the Army George W. Dunaway. Public Domain Image by the United States Army.

A burial at Arlington National Cemetery in 2008 for Sergeant Major of the Army George W. Dunaway. Public Domain Image by the United States Army.

It’s the last weekend in May and for many that’s a weekend to head “down the shore” as we say in Jersey, for the first time of the season. And while there are many who kick off what is informally, the “first weekend of summer,” Memorial Day’s true meaning was not defined as a time to crack open a beer, or to light the barbecue grill and slap on some steaks.

Turn back the clock instead to 148 years ago, May 1868. Earlier in the month on May 5, General John Logan, who had been the commander of the Civil War’s Union side, drew up a proclamation via “General Orders No. 11.”

General Orders No. 11 specified that on May 30, 1868, residents across the then much smaller nation were to honor those who “died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet church-yard in the land.”

It was Logan’s wish in this proclamation that year after year, those who remained would honor those who perished.

“Let us, then,” he penned, “at the time appointed gather their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with the choicest flowers of spring-time; let us raise above them the dear old flag they saved from dishonor; let us in this solemn presence renew our pledges to aid and assist those whom have left among us a sacred charge upon a nation’s gratitude, the soldier’s and sailor’s widow and orphan.”

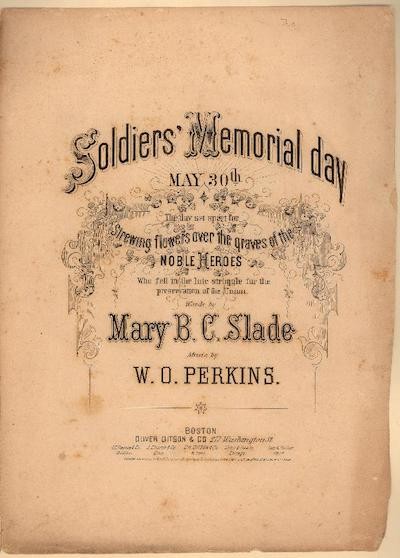

A Decoration Day Card to honor those who died during the Civil War. Copyright to the respective owners.

Rather than Memorial Day, this day was then called “Decoration Day,” with 20,000 graves of loved ones on both the Union and Confederate sides in Arlington National Cemetery, showered with flowers, gratitude and respect for what those soldiers gave.

New York State became the first in the republic in 1873 to adopt Decoration Day as a day of remembrance. The rest of New York’s northern neighbors followed suit by 1890. The southern states would not join in remembrance on the same day as the north, and finally joined in once the day of remembrance fell into a holiday that honored all American military, which occurred after World War I.

World War I brought its own angle and traditions to what we now know as a part of our current Memorial Day. Poppies, a blood-red flower began popping up among the graves of soldiers who perished during the war, notably in Flanders. Flanders is a region located in Belgium, and is where one of the first chemical attacks that ever happened in wartime battle occurred.

Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae was one of those soldiers in Flanders, fighting with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. McCrae enlisted not only as a medical officer but joined the cause as a gunner.

McCrae survived that chemical attack during the Second Battle of Ypres on April 22, 1915, with he and his fellow Canadians holding German forces back for a two-week period, in spite of what McCrae wrote to his mother was a “nightmare.”

“For seventeen days and seventeen nights,” he wrote to his mother, “none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds…and behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.”

McCrae buried his friend, Alexis Helmer, who died in battle on May 2. He observed the poppies push through the ground quickly while in Ypres, and enveloping the graves of those who lost their lives, including Helmer’s grave.

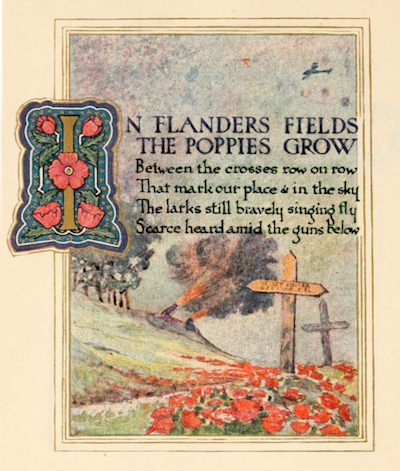

“In Flanders field the poppies grow,” McCrae, also a gifted poet, began to write the day after Helmers’ burial as he sat in the Advanced Dressing Station in an ambulance, a site in the Ypres area now called the “John McCrae Memorial Site.”

“Between the crosses,” he continued, “row on row, that mark our place; and in the sky the larks still bravely singing, fly, scare heard amid the guns below.”

Click below for a video of the poem in song version.

Taking the poem from the perspective of those like his friend Alexis Helmer, McCrae then wrote. “We are the Dead. Short days ago we lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, loved and were loved, and now we lie in Flanders field. Take up our quarrel with the foe: to you from failing hands we throw the torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die we shall not sleep, though poppies grow in Flanders field.”

In the first line the word “blow” and “grow” are interchangeably used, so the line often also reads, “In Flanders field the poppies blow.”

McCrae reportedly created the poem within 20 minutes, with Helmer in mind, with those around McCrae watching him write in between patients, and also while glancing at his friend’s grave. After reading it to those in his unit, he was encouraged to send it in for publication.

Punch, a magazine from the United Kingdom, published McCrae’s poem on December 8, 1915.

Moina Michael, another poet, was the one who conceived of the idea about Memorial Poppies. The poppies, as they are crafted today, were created to sell to raise funds for those who served in the military, who required assistance. In France, a similar movement began, with created poppies sold to benefit widows and orphaned children following World War I.

Today, the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), an organization that helps veterans and their families in need continues to sell poppies to benefit those families. Veterans in VA hospitals often help to create these poppies by hand. This tradition began in 1922, with the flowers coined “Buddy Poppies,” as veterans injured in the war helped the VFW to create the poppies, which is the VFW’s official memorial flower. The VFW is the only organization that can make and sell Buddy Poppies, with the VFW having received a patent and trademark right for the revered flower on May 20, 1924.

Click below to watch a video about the assembly of the Buddy Poppy:

Today, the VFW still supports veterans’ causes for rehabilitation efforts, provides compensation to injured veterans who craft the poppies, and also provide some support to the VFW National Home for Children. The VFW National Home for Children assists military and veteran families and VFW descendants.

It was not until May 11, 1950 that the United States Congress resolution declaring Memorial Day was passed under President Harry S. Truman.

“WHEREAS in tribute to these silent dead it is fitting that we lift up our voices in supplication to Almighty God for wisdom in our search for enduring peace,” was typed in the 1955 “Prayer for Peace” Proclamation that President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed. “WHEREAS the Congress in a joint resolution approved May 11, 1950, provided that Memorial Day should be set aside as a day of prayer for permanent peace, and requested the President issue a proclamation calling upon the people of the United States to observe each Memorial Day in that manner.”

In 2000, Congress initiated the National Moment of Remembrance, a Public Law that is observed at 3 p.m. each Memorial Day. President William “Bill” Clinton signed off on it, and now a range of organizations and venues stop at that time to remember the fallen for a moment of silence. Amtrak trains numbering 200 whistle in honor, while nearly 500,000 Major League Baseball spectators across the country bow their heads in remembrance. Other places that observe the moment are: the Liberty Bell, Empire State Building, Statue of Liberty, National Constitution Center, Delaware Park, and NASA.

On Memorial Day itself, major cities host large parades, and flags across the nation, and in Puerto Rico, are flown at half-staff until noon.

Editor’s Note: Please reflect on this Memorial Day and each one following to remember those who gave for our freedoms throughout every war, since the inception of the United States.

Like this story? Stay on the scene with InsideScene.com. Click here to follow us on Facebook.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.